ACUFO-1944-09-18-MOUNTDECEPTION-1

Published in the USA, Fate Magazine is the first magazine about Fortean and paranormal phenomena, and it is well known that it was the first to report the famous 1947 sighting of pilot Kenneth Arnold, newspapers excepted. Fate was started by Raymond A. Palmer, editor of the SF magazine Amazing Stories and Curtis Fuller.

The December 2001 issue published an article about a 1944 plane crash in Alaska, insisting that the crash was mysterious because none of the bodies of the crew and passengers were found when rescuers came at the crash site. The Fate story then appeared on one ufology Website.

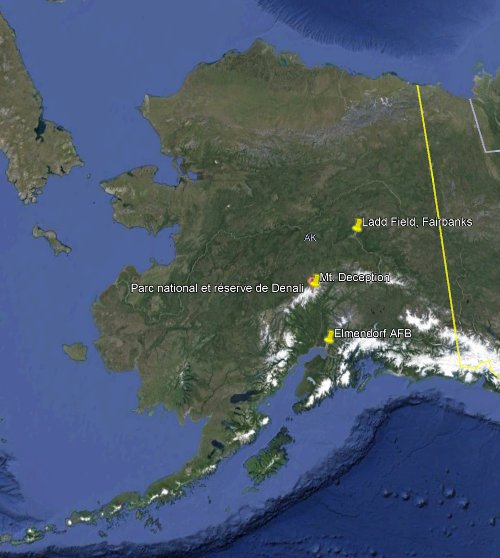

The story of the crash is well narrated in several non-ufology publications. In short: on September 18, 1944, a C-47 of the Air Training Command left Elmendorf AFB at Anchorage, Alaska bound for Ladd Field in Fairbanks, Alaska with a crew of 3 men and 16 passengers. It was a routine flight during clear but turbulent weather, but the plane never arrived at Ladd Field.

It was found that it crashed on a mountain later called “Mount Deception”, near Mount McKinley, Alaska. The most extensive and daring rescue expeditions ever undertaken was started. It was a tremendous and difficult task to get to the wreckage, and it served as a model for future operations of this kind.

It is true that the expedition did not find the bodies, but this was not so mysterious: there was 10 feet of snow over the debris. The debris were scattered, the C-47 had broken down in pieces over la large area, and the bodies were certainly ejected, widely scattered on the terrain, and covered by 10 feet of snow.

So, there was no reason at all to speculate that aliens abducted the crew and the passengers.

| Date: | September 18, 1944 |

|---|---|

| Time: | 12:00 |

| Duration: | N/A |

| First known report date: | 2001 |

| Reporting delay: | Decades. |

| Country: | USA |

|---|---|

| State/Department: | Alaska |

| City or place: | Mount Deception. |

| Number of alleged witnesses: | 0 |

|---|---|

| Number of known witnesses: | N/A |

| Number of named witnesses: | N/A |

| Reporting channel: | Fate Magazine. |

|---|---|

| Visibility conditions: | Bad weather. |

| UFO observed: | No. |

| UFO arrival observed: | N/A |

| UFO departure observed: | N/A |

| UFO action: | N/A |

| Witnesses action: | N/A |

| Photographs: | N/A |

| Sketch(s) by witness(es): | N/A |

| Sketch(es) approved by witness(es): | N/A |

| Witness(es) feelings: | N/A |

| Witnesses interpretation: | N/A |

| Sensors: |

[ ] Visual:

[ ] Airborne radar: [ ] Directional ground radar: [ ] Height finder ground radar: [ ] Photo: [ ] Film/video: [ ] EM Effects: [ ] Failures: [ ] Damages: |

|---|---|

| Hynek: | N/A |

| Armed / unarmed: | Unarmed. |

| Reliability 1-3: | 2 |

| Strangeness 1-3: | 1 |

| ACUFO: | Not UFO-related. |

[Ref. ubc1:] "UFO*BC" WEBSITE:

|

Cover from Fate Magazine, Dec. 2001 shows C47 over crash site on Mt. Deception, Alaska Source: “Fate” magazine - December 2001, pages 14 and 15 “The Mysterious Mount Deception Wreck”

|

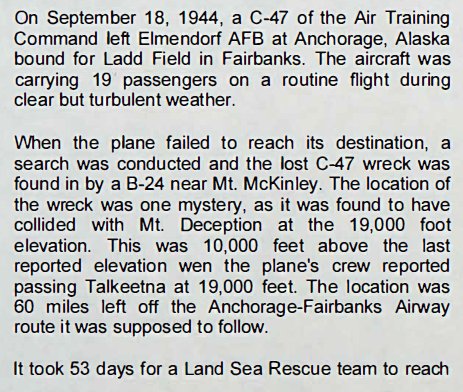

On September 18, 1944, a C-47 of the Air Training Command left Elmendorf AFB at Anchorage, Alaska bound for Ladd Field in Fairbanks. The aircraft was carrying 19 passengers on a routine flight during clear but turbulent weather.

When the plane failed to reach its destination, a search was conducted and the lost C-47 wreck was found in by a B-24 near Mt. McKinley. The location of the wreck was one mystery, as it was found to have collided with Mt. Deception at the 19,000 foot elevation. This was 10,000 feet above the last reported elevation wen the plane's crew reported passing Talkeetna at 19,000 feet. The location was 60 miles left off the Anchorage-Fairbanks Airway route it was supposed to follow.

It took 53 days for a Land Sea Rescue team to reach

the site, traveling by snow jeeps and sleds, resupplied by air drops by another C-47 Gooney Bird. When the rescuers reached the wreck, they did a thorough search of the site to determine the cause of the crash. The main part of the wreckage was found on a snow avalanche which had been initiated by the collision. It was determined the plane had hit the mountain at cruise speed, splitting open the fuselage and ripping the wings off. The port engine and propeller were found embedded in the ice near the peak of the mountain, but most of the wreckage had tumbled 1500 feet down the mountain where it lay in a mass of crumpled metal.

The plane had been carrying a full load of fuel, but there was no evidence of any explosion or fire. No baggage was found, but the pilot's B-4 bag containing an unbroken bottle of whiskey wrapped in cotton shorts, was found outside the cabin. The biggest mystery was that despite an extensive search, no bodies or traces of flesh, blood, hair or body pieces were found with the wreckage or at the impact site.

What happened to the passengers and crew? The account is somewhat reminiscent of many similar accounts where wrecked and abandoned aircraft and ships are found without any trace of the crew and passengers. Did the crew and passenger's abandon the aircraft before the crash or were they perhaps taken from the plane, by someone or some force before the collision of the aircraft with the mountain?

C-47, nickname “Skytrain”, was the designation of one of the US Army Air Forces' military versions of the Douglas DC-3 transport aircraft. It was used on all fronts during World War II. More than 13,000 DC-3 were built, several of which are still flying in 2024.

|

|

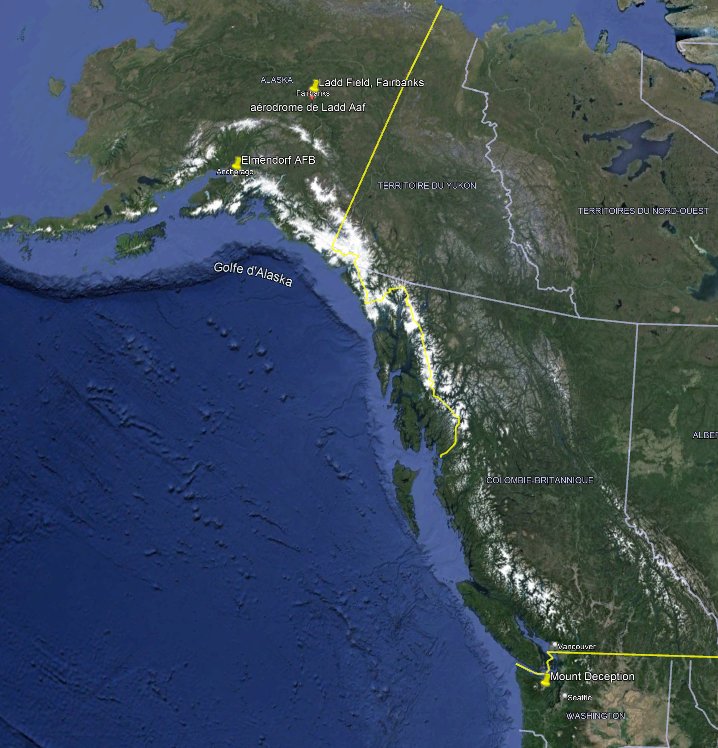

The report in [ubc1] citing Fate Magazine tells that the C-47 took of from “Elmendorf AFB at Anchorage, Alaska bound for Ladd Field in Fairbanks”. It thus makes no sense that the plane crashed on Mount Deception, not 60 miles off-road, but 1300 miles off-road, in a totally wrong direction as shown on the map below:

|

Information on www.baaa-acro.com/crash/crash-douglas-c-47a-90-dl-mt-deception-19-killed :

The crash took place on September 18, 1944 at 12:00 Local Time, the aircraft was Douglas C-47 Skytrain (DC-3) 43-15738 of the US Army Air Forces with a crew of 3 and 16 passengers.

“En route, while flying in marginal weather conditions and at insufficient altitude, the aircraft hit the slope of Mt Deception located in the Denali National Park. All nineteen occupants were killed.”

The National Park Service at www.nps.gov/articles/denaliwwiiplanecrash.htm tells that a 44-man mission traveled through dangerous conditions to seek the wreckage of an US Army C-47 aircraft after it crashed into Mt. Deception On September 18, 1944:

An aerial reconnaissance taken a few days later confirmed that all aboard had immediately perished. The Army Air Corps' Col. Ivan Palmer, however, demanded to know more details about the crash, so he asked current Park Superintendent Grant Pearson to fly over the area. After that October 2 reconnaissance, the Army asked Pearson if he could head a rescue party to the crash site. Pearson demurred, stating that it would be too risky to descend a 50-degree, icy slope for a body-recovery operation. Palmer and his higher-ups, however, explained that the son of a Congressman had died in the crash, making a trip to the site virtually mandatory; and furthermore, the military could draft Pearson for the purpose if he chose not to volunteer.

Under those circumstances, Pearson dropped everything and organized a 44-man rescue expedition. On October 10, he and others boarded two military “snow tractors” and drove through a blizzard to Wonder Lake; they then headed south to McGonagall Pass and on to the upper Muldrow Glacier. Recognizing that most of his expedition members had little winter expedition experience, Pearson asked experienced climber Bradford Washburn, camped at nearby Wonder Lake, to lend a hand, and on November 1 the snow tractor brought Washburn up to Pearson's camp. the two men led a party of twelve over the Alaska Range and, clinging onto ropes, down to the crash site. The men found undisputable evidence from the crash-blood on the fuselage, a canvas suitcase, a whiskey bottle, and other items-but a recent ten-foot snowfall frustrated all attempts to locate any of the victims' bodies. The men then retraced their steps to Muldrow Glacier, where the remainder of the test expedition crew was camped. They then continued onto Wonder Lake. After that, Pearson and his team were flown back to Elmendorf Field. The last of the expedition arrived there on November 24, almost two months after the rescue effort began.

Another source is Cpl. Paul Lowney, who wrote the article “Tragedy of the C-47” in “Alaska Life, the Territorial Magazine”, Alaska Life Publishing Company, April, 1945:

By Cpl. Paul B. Lowney

On September 18, 1944, nineteen persons -- nearly all soldiers returning to the United States on furlough -- climbed into an A.T.C. C-47 transport plane at Elmendorf Field, Anchorage. The motors warmed for a few moments and then the plane lifted easily into the sky and circled north. There was nothing unusual about this. In a matter of hours the plane would land in Fairbanks and the flight would become only a notation on forgotten paper.

But the flight was no ordinary one. The plane, which might have landed safely in Fairbanks, mysteriously crashed into solid ice on an unnamed, uncharted peak sixteen miles northeast of Mt. McKinley and sent crew and passengers tumbling through the fuselage into the deep snow, never again to be seen by human eyes.

This routine flight brought about one of the most extensive and daring rescue expeditions ever undertaken. For the first time men were to investigate a towering, cone-like peak of ice stretching skyward for 11,400 feet.

Pilot Roy Proebstle, flying at 9,000 feet over Talkeetna station, reported to Ladd Field, Fairbanks, at 7:42 A.M. Half an hour later the plane was estimated over Summit, still on course.

As hours slipped by, Ladd Field saw nothing of the C-47. Silence added more certainty to a growing fear for its safety. Drafts and currents over the snow-capped Alaska Range are known to be treacherous; peaks are high and deceiving; thickly falling snow obscures visibility. Clouds often hang low, screening huge blocks of ice that jut miles into the sky.

Killed in the plane were:

RAY PROEBSTLE, pilot, Minneapolis

L. H. BLEVIN, co-pilot, Minneapolis

Pvt. J. A. GEORGE, Jr., Russelville, Ark.

S 1/c BERNARD ORTEGO, Opelsas, La.

Maj. RUDOLPH F. BOSTELMAN, La Grange, Ill.

Pvt. CHARLES E. ELLIE, Greenfield, Ill.

Lt.(jg) ATHEL L. GILL, Nashville, Tenn.

Lt. ORLANDO J. BUCK, Rosebank, N. Y.

T/4 TIMOTHY d. STEVENS, Suffern, N. Y.

Pvt. HOWARD A. PEVEY, Roseland, La.

Pfc. ALFRED S. MADISON, New Auburn, Wisc.

Pfc. CLIFFORD E. PHILLIPS, Lake City, Tenn.

Cpl. CHARLES N. DYKEMAN, Holland, Mich.

T/5 MAURICE R. GIBBS, Caro, Mich.

Pvvt. ANTHONY KASPER, Allamucky, N. J.

T/5 EDW. S. STOERING, Duluth, Minn.

Sgt. WM. E. BACKUS, Lake Wales, Fla.

CWO FLOYD M. APPELMAN, Akron, Ohio

CARL V. HARRIS, Texarkana, Texas

Three days later, September 21, the shocking truth was known. An ATC pilot sighted wreckage on a barren, white peak between Mt. Brooks and Mt. McKinley, but he saw no signs of survivors.

September 30, Grant Pearson, chief ranger of Mt. McKinley National Park and a mountain climber with 20 years experience, was called to the Land Rescue Office at Elmendorf Field to organize the expedition which Gen. Delos C. Emmons of the Alaskan Department and Gen. Davenport Johnson of the 11th AAF so keenly supported. After several flights over the crash area, Pearson and his pilot spotted sections of the plane over the glistening snow.

When Pearson reported back to Col. Ivan M. Palmer, CO of the Elmendorf Airbase, the Colonel turned to him gravely and inquired: “Can you get to the plane?” Pearson answered simply, “Yes.”

And so began one of the largest land rescue expeditions ever assembled. The job was herculean. Pearson -- a tough, hard-bitten, husky mountain-man -- outlined his needs. He would require at least 40 men trained in mountain-climbing, bulldozers, trucks, tents, radios, stoves, tractors, gasoline, mountain-climbing equipment and dozens of other items to aid men against winter and the dangerous, glacier-capped mountain. Some equipment had to be flown in from the States, some came from the Aleutians. Finally it was all assembled and men and supplies moved by train to McKinley Park headquarters.

The expedition, under the direction of Capt. Americo R. Peracca and Lt. Allen M. Dillman, was to consist of a series of camps several miles apart leading to the scene of the crash. Base camps would be largest; those more advanced would be smaller. With snow jeeps, trailers, trucks, tractors, and several tons of supplies, the advance party began pushing its way through the heavily drifted snow toward Wonder Lake. Bulldozers first had to clear the road. At Wonder Lake the men set up camp and then pushed on to Cache Creek and established another.

From here a few traveled by foot to the top of McGonagall Pass, against what Grant Pearson described as the hardest wind he had ever seen in the Pass. They set up camp here, contacted Wonder Lake by radio, and waited for a plane to drop much-needed supplies.

By extraordinary coincidence, Bradford Washburn and a few Army officers were testing emergency and survival equipment for the Army Air Forces in the vicinity of Wonder Lake and were only a few miles from the camp of the rescue party. Through special permission of Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio, Washburn was allowed to join his old-time mountain-climbing friend, Pearson, and aid with the rescue work. Though small of stature and slight of build, Washburn possesses unusual stamina, and is regarded as one of the nation's outstanding mountain-climbers and geographers. At the age of 1 he climbed the Swiss Alps and later published three books for children on these experiences. In 1942, together with Pearson, he scaled the highest pinnacle of Mt. McKinley. His present work with the Air Technical Service Command, testing personnel equipment, brought him to Alaska.

In a snow jeep S/Sgt. James E. Gale, T/4 John M. Greany (a photographer), Washburn, and Pearson left McGonagall Pass and proceeded up the glacier. Going at first was not steep, but slow. A dangerous avalanche slide took considerable time to pass. At 7,500 feet the men abandoned the metal crampons to their shoes, and went slowly up a step, icy grade. For 200 feet steps had to be cut in the ice, but at the top of the pass they got a good view of the crashed plane over 1,000 feet below them.

At this time Ranger Grant Pearson wrote in his diary: “From the top of the pass we have a good view of the airplane. There is a real steep grade down to it. When we were at about 11,000 feet an airplane flew over us. We were then in our most difficult position, perched on the side of the mountain, cutting steps in the ice.”

With the aid of ropes and steps hewn into the ice, the men made their way still farther upward to a ridge immediately above the crash. Choosing a camp site, they sent for additional men from a camp below. Washburn, Pfc. Jack N. Yokel, and T/5 Jacob A. Stalker left the ridge camp in the morning and placed 650 feet of rope down the hazardous grade to the plane. Ten men from the ridge camp descended the rope to the C-47. Near the wreckage they found supplies which had been dropped by plane previously.

Immediately the men began clearing snow from the twisted fuselage. One section of the plane was broken off just above the rear toilet near the vertical stabilizer. The tail wheel was intact. To the right of the tail they found the remains of the pilot's cockpit. Most of the instruments were uncovered, but completely ruined.

No bodies or traces of bodies were found.

Some personal items were uncovered. A flight bag was undamaged. Nearby were a pilot's cap and a toilet case. There were some playing cards strewn in the snow, a few snapshots, a mathematics book belonging to Karl V. Harris, a civilian. Also uncovered were a soldier's furlough papers, some chewing gum, a pack of cigarettes.

After some seven and a half hours of digging still no bodies had been found.

The next day they again dug. The futility of trying to find bodies was indicated in Pearson's diary for November 13: “Wind blowing hard this A.M., and it is cold. We dug out the balance of a wing and also a section of the fuselage. There were no bodies in it or any baggage. There is ten feet of snow over the airplane. We have dug out the main parts of the airplane . . . but have failed to find any bodies. The question is where next to dig. We dug eight hours today. Weather windy and cold.”

The motor of the C-47 was buried in the ice near the summit of the pass, over 1,000 feet above the fuselage. Pvt. Elmo Fenn, S/Sgt. Richard C. Manuell, S/Sgt. James Gale and Washburn left the ridge camp and climbed to the cornice of the peak above the motor and established a fixed rope. Gale and Washburn went down the rope to the motor, inspected it, and determined it to be the left one. Scattered about they found engine mountings, propellers, and some tubing.

There was nothing more the expedition could accomplish. They found the plane, identified it, excavated as much wreckage as they could, an made certain there were no bodies in it. But still the enigma of the C-47 remained: (1) Why did the plane crash point-blank into the icy mountain? (2) What happened to the bodies?

Theory and evidence point out logical answers. The plane was reported flying under icing conditions, which may have prevented it from securing necessary altitude to clear the mountain. As for being nearly 50 miles off course, it had been pointed out that radio beams have been known to bend. Still another theory, and a probable one, is that the plane was caught in a severe downdraft and could not pull out. Such a downdraft sucked Pearson and his pilot down 1,000 feet when flying over this area in a bomber. Actual cause of the tragedy is at best conjecture. A high-ranking Air Corps official put it: “Only one man knows the real cause. . . and he's not here.”

As to the bodies, opinion is in accord. Pearson, Washburn and other members of the search party agree that the occupants of the plane were hurled out when the motors struck the solid ice, splitting the fuselage open. Bodies and other heavy object which were loose inside the plane were thrown out into the snow and likely fell into crevices on the mountainside. The impact of the crash caused a snow-slide which concealed all evidence which might otherwise have been found.

According to official reports of the Air Corps, recovery of the bodies -- even in the spring when weather is more suitable -- is highly problematical. At this altitude only summer snows thaw. Owing to the location of the wreckage, prevailing winds, and depth of drifted and packed snow, excavation in the spring would be practically impossible. Since no bodies were found in the fuselage and surrounding debris, a strip approximately one-quarter-mile long, from the point of impact to the resting point, would have to be dug up. Even if this were done, there is no assurance that the bodies could be recovered, for there is every likelihood they have lodged in crevices.

The Indians had a name for the mountain, although it is little known. They called Mount McKinley “Denali,” meaning “home of the sun.” Mount Foraker, nearby, they called “Denali's Wife,” and the remainder of the peaks -- including the one on which the C-47 crashed -- were known as “Denali's Children.” Now the peak will likely take the name of the senior officer aboard the ill-fated ship (Major Bostleman) or one of the several names suggested by members of the rescue party: Deception Peak, Crash Mountain, or Furlough Peak.

No one can minimize the stark tragedy, the shock, and pathos in the loss of the men aboard the C-47. A worse aircraft disaster in Alaska is not known. These men were not engaged in combat -- where death is expected -- but were passengers bound for the States after many weary months in Alaska. This type of death in uniform is not expected yet it sometimes happens.

In a larger sense, it may be said their lives were not altogether given in vain. Survival and rescue work in Northern terrain is relatively untried. As air travel increases in Alaska, more planes will crash, others will be forced down, and still others will be abandoned by parachute. This is inevitable. Whether personnel of these unfortunate flights live or die on barren, cold, mountainsides will depend largely upon how much is known about survival. Whether or not help will reach them in time will depend upon how much is known about rescue.

On the McKinley expedition invaluable information was learned both on rescue and survival. Men spent six weeks in the field learning how to live and get along with their equipment. Much was learned about the use of communication, dropping supplies by aircraft, mechanical equipment, tents, clothing, and food. Dozens of pages were written on the usefulness of each item and whether or not it could be improved, and how. Much was learned about the organization of rescue parties and how crash victims may be gotten to quickly and efficiently. As a result of the recent rescue attempt, there can be no question but that the whole knowledge of survival and rescue in the North has been advanced substantially.

Not UFO-related.

* = Source is available to me.

? = Source I am told about but could not get so far. Help needed.

| Main author: | Patrick Gross |

|---|---|

| Contributors: | None |

| Reviewers: | None |

| Editor: | Patrick Gross |

| Version: | Create/changed by: | Date: | Description: |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | Patrick Gross | April 24, 2024 | Creation, [ubc1]. |

| 1.0 | Patrick Gross | April 24, 2024 | First published. |